OPENING SEAS(ON) - WDP TRIP 7

- mandog

- Aug 1, 2018

- 15 min read

Updated: Mar 7, 2019

Summarizing the seventh trip of the 2018 Wild Dolphin Project field season

August 01, 2018

Tomorrow would be the opening season for lobster and the seas were on! A mate from the year before and I were running the trip as co-captains. We would be sharing in the responsibilities and rock, paper scissored for the captains quarters. It went four rounds, but I lost at the end. The minute our bow broke past the outgoing tide line of the Lake Worth inlet the seas began to pound. Stacked together were the three to five with occasional six foot seas. I kept the Eisenglass down as the bridge was taking a lot of spray. The waves were heaving us into a steady rocking rhythm and everyone hunkered down in their bunks. They did not let up until we came within a thousand feet of Bahamas' West End. We had an easy clearing at customs as all our paper work was done with perfection. You'd think by the seventh trip we ought to, right?

By five o'clock we were out the inlet and steaming towards our anchor spot. The wind was still whipping, but we had it to our stern finally. Not too far from our anchor hold we got a jolting surprise! A group of six spotteds barreled towards the boat. The stomping on the bridge signal went out and a very excited to see us group of dolphins were awaiting our entry. They looked to be in a playful mood so we didn't waste time getting folks ready for the water. As for passengers on this trip, we had a group of four ladies that were all born in the forties. All of which had been recurring guests with The Project, going as far back as the eighties. Needless to say, they knew their way around the boat. The same protocols as always were in place for guests' safety. Keeping a close eye on them while in the water and ensuring stability when moving around on the boat. However, when there were dolphins, age was not factor for this fun bunch of ladies as they eagerly slipped into their fins and pulled the swim caps down tight. Their amusement from the dolphins is always refreshing. Something about these animals keeps a lot of people coming back over the many years. Each person having their own personal connections and motivations towards it.

The water was crystal clear, despite the heaving seas. We got our swimmers into the water no issue and the dolphins were on! It was a total of six dolphins, with three sets of mother and calves. One mother, Zipp, they'd not seen in three years, which meant the new calf traveling alongside her could now get an identifying name. Over dinner the next few nights we thought up Z names to follow in the alliteration theme and finally landed on Zest. The other Naia and her calf Nala had been documented on LBB this season already. The last duo, Spring and Summer, were regular sightings on the bank. When dealing with calves of that age (1-3 yrs) they are of an energy unlike anything else I have seen in the ocean. And when one of the mothers scoops up a piece of sargassum, it signals to the calves that its now an okay time to play and oh boy, let the games begin !!

The mother passes off the sargassum (sea plant) and one of the juveniles takes it in their mouth, nibbles on it for a bit and then lets it fall to their pectoral fin. It seems they are unable to independently wiggle their pec fins, so when they do an action on one side its mimicked identically on the other side. It's funny to us because it appears as if they're wiggling their 'arms' like an excited child. The wiggling, however, is a series of calculated body movements that allows the sargassum to inch its way down to the edge of the pec and then be dropped into the water only to be snagged by the tail fluke last second. It's a maneuver that seems accidental, but couldn't be any less than calculated and perfected over the course of a lifetime. As they swim with it, sometimes the other juveniles cannot wait for their turn and will swim past and steal the sargassum from the fluke, repeating the process all over.

The juveniles were flying around with so much energy, it seemed like they could not be contained. They pump their tails hard, blast to the surface, grab the quickest puff of air and glide straight back down to the bottom in a static descent. At the bottom, like their mothers, they use echolocation clicks as they forage.

In one moment, a lazy loggerhead had stumbled into the mix. It was trying to figure out a course to take to avoid these swarming juveniles. When it had found itself surrounded by their buzzing erratic loops, it staggered about from one side to the other, unable to find its way through. It bolted past them and their fun moment was over as the turtle got away unscathed. When juveniles are acting out, in a way that is not good for social order or could perhaps be dangerous to the calf itself, they are disciplined by their mothers. It's a very tight bond that requires this oversight because 'becoming a dolphin' is not something they are born with. It is a learning exchange from their peers and mother. Ordinarily, they swim directly on the flank of the mother, known as an echelon position and from here can be seen peeking around the side, inspecting things as they go. They were also nursing, which is a valuable moment to capture on film for research. All of these behaviors go towards the catalogue of information, which tells the dolphin story. I see the research as the something like a dolphin narrative. A lot of hard line science goes into studying and interpreting that data, but mostly its just hitting the record button, watching what they do and communicating to the world what we have witnessed over the years.

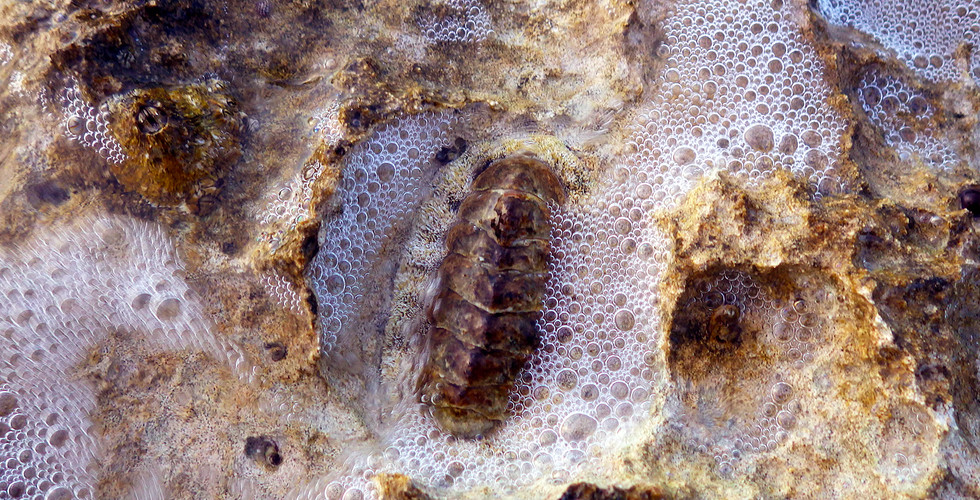

The next day, we motored out in the still sloppy, choppy, cresting swells and found the Sugar Wreck empty and awaiting our vessel. There were little Bahamian skiffs floating near by. The locals were putting in swift action to claim all the lobster tails they could before the non-natives get there and harvest their precious resources. I heard them chatting on VHF channel 16 all day long, talking about how many they got and how many got away. Most freedive, but for the deeper areas, some use a hookah rig which is a long hose connected to an air compressor. They are likely bare handing them. If a lobster makes a darting flee from the makeshift 'condos', there's likely no chance of catching it out in open grounds unless it holes itself up again. The condos consist of a piece of aluminum roofing with wooden 2 x 4's tacked underneath to give it just enough room for lobsters to back in and feel the protection of its cover. Lift up a lucky lid and there could be a hundred lobsters beneath a 6 by 8 foot piece of metal.

We caught Sugar Wreck at a nearing slack high tide, so it was perfect conditions, short of the rolling, breaking swells of course. Beneath those seas was total divinity. Today you could see from one end of the wreck to the other. All of the usual Sugar Wreck characters were in their usual spots. The schools of blue striped grunts huddled en masse in the middle. Big, thick Bermuda chubs moving around above them. The yellow tail damsels, rock beauties and French angels all congregating around the corals. The puffer hiding in its same crevice. Early on I got a look at the resident hawksbill before he took off to leave us the wreckage to ourselves. I figured he'd be back, so now knowing his spot, I kept an eye on that area for his return. Beneath the wreck I saw the gills of a teeny nurse shark flicking in and out. It moved about the wreck, slipping from one covered hiding place to another. I spotted a large lion fish hiding upside down beneath one of the folds of the wreckage.

(images: porcupine pufferfish, hawksbill turtle, ribbon coral and brain coral)

A few groups of swimmers had gone back to the boat and new buddy pairs had come in just as the hawksbill was making its return. I let everyone know and worked my way over to it, taking a long, wide path sure not to scare it from its spot in the sand. It was there inspecting the tall sponges, as if deciding whether it had an appetite or not.

I closed in well enough to get some good pictures of its amazing shell coloration and then put the camera down to stare at one another for a bit. It perched itself at an angle, as if to say, "Any closer and I'll have to flee," but I held firm and it settled down, noticing I would not come any closer. I swam for over an hour and a half and the conditions never changed. I did my usual sub-surface meditations, sitting on the metal platforms and holding my breath for upwards of two minutes. At this depth (15-20ft) I am really dialed in. Whenever someone would swim over top of me, I'd give them a wave and send up a bubble ring. I'd close my eyes, feel the heart beat slow to match the rhythm of the surging ocean and when I'd open... be greeted by the sight of a different fish each time staring back at me. I love the dull, quieted, peaceful sensations of being underwater. I love the feeling when the mind becomes still and the ocean has put everything into a connected flow state. The corals wave and dance. The fish hang in suspension, swinging with the waves. Even beneath the wreckage, the small pebbles can be heard rolling around to the same cadence.

As usual, I had to be pulled away from this dream and was last to leave the water. I did a quick inspection of the hull, noting the running gear and if any obstructions were on the intakes. Everything looked good so I climbed out and breathed a big happy sigh of delight. Everyone was grinning from their swim. I rinsed off and continued to glow from the state of ocean bliss I was in. We had to turn back into the seas now, which meant for a rough ride. The pounding had returned and we realized today would not be conducive to getting in the water with any dolphins.

We worked our way back and checked out an area we'd seen the dolphins the day before. No luck. So at 1600 turned it around and decided to put down anchor early. This gave me some time to work on a few projects I had in mind. I got right into zip tying some cut garden hose to stop the aluminum ladder from rubbing on itself while it's in the folded upright position and brainstormed on how to use a similar approach to protect where it pinches against the platform while in the folded down position. After a few attempts, I had a worthwhile solution using some of the tricks and techniques I'd picked up from a previous captains' work. I'd seen in the engine room where he had protected some lines from rubbing against each other. After that I went around and soaped up the railings and windows and gave the deck a rinse down. I put a Eisenglass treatment on and went down to the aft deck to enjoy the breeze and summer heat lightning.

It was taco night so I waited for everyone to make their way to the picnic table before going in. They were especially delicious tonight. I made two and sat back in the fighting chair with it reclined all the way to watch the beginning of the star show.

The planets are always first: Venus, Jupiter, Mars and Saturn. And then the bright stars come out like Vega, Altair, Deneb forming the Summer Triangle. Soon Ursa Major is out, giving us Polaris, Ursa Minor and wrapping around it is Draco. Once the skies get darker, the Milky Way is seen running through the neck of Cygnus. Up high, the northern crown, or Corona Borealis is visible. We talked about what signs we are and I showed the Scorpios where their sign was as its a great time of year for it. It was a clear night and we all got a chance to see a shooting star go halfway across the horizon. A little after 2200 I started the water maker and went in to take a shower. The harder I work, the better I sleep, so tonight would be a good payoff.

The crossing to Bimini was one of the worst ones yet, with waves reaching maximum heights of six to eight feet. As usual, the deep water edge leading into the New Providence channel were the worst parts requiring that I handle the waves with a lot of technical maneuvering to find lines that dodged as many giant swells as possible. When one would rear up, showing it would take us on the beam, I would counter by driving straight at it and engulfing the boat into a hard rocking spray. A couple of double bell ringers happened from the impact being so hard that the boat lurched over the successive wave and rang a second time. At fifteen miles in, and with having to constantly edge our bow into the seas, we were off course by ten degrees. When the seas finally reduced themselves to a more manageable size, I could carve between the sets to get us back onto our heading. It still meant I had to be on high alert and a few times I jumped from the chair, shut off the autopilot and cranked hard into the face of a few wave sets. Arriving in Bimini, we were treated to an early encounter with three to four of the Bimini bunch. At 1800 we were putting down anchor.

The winds were showings no signs of relinquishing their control of the ocean, which meant, we had been reduced to our usual, tight to the island work space. The first day in Bimini began with a bottlenose spotting near the inlet. In the shake down the day prior, we had disconnected a hose going from the fresh water reservoir to the pump that delivers water to all of the boat. We spent some time fixing this. Re-priming the pump by disconnecting all hoses and filling with water so no air gaps would be in the lines and allow the pump to run properly. In the time of doing this, we later rejoined possibly the same group of bottlenose, but this time they were double their numbers. They were crater feeding as well, which meant they were working a very tight area with little-to-no traveling, scanning the sandy bottom searching for fish underneath.

It was a great encounter to get in the water for. During the swim, a group of five spotteds in a tight formation cruised in and got right into the mix. Sometimes, the two species forage adjacent to one another, although they eat different fish and the bottlenose often dig deeper into the sand. It was a peaceful encounter with no aggression towards each other.

We put down anchor for lunch at the Bimini squares, a local GPS number we keep for snorkeling near to shore. It looks to be an artificial reef structure and was likely put out by one of the resorts. Its depth is around eighteen feet, which makes it good for us to anchor at. Our hose repair earlier had tightened one side, but now the other side had come loose and we lost water pressure again. The process, while still hot and tiring in the confined, dimly lit, back spaces of the engine room went a little quicker being the second go at it. We quick ate our lunches and were then treated to juicy slices of watermelon. If that didn't rejuvenate the system, I don't know what would !!

We managed to get up to Hens and Chicks one day for a snorkel swim as well and were treated to the spot all to ourselves. It was a fantastic swim as usual.

(Sea fans and porous sea rods, stoplight parrotfish, honeycomb cowfish, lion fish)

We got down and cruised along the edge a little more. On the way back to the anchor hold, we were headed through what I refer to as, "The Gauntlet." Due to the confined area of Bimini's deep water edge and its shoreline, it leaves a thin space for the dolphins to locate themselves. Without fail, we always cross paths with them right at the time I am dead-eyeing the anchor spot or have just heaved the anchor first thing in the morning. At 1725 we came into a group of twenty to thirty dolphins. It would be the encounter of the trip, no doubt. They were so close together it looked like a car crash. We rotated in different groups of passengers and interns and they seemed to be behaving quite impressively. Perhaps a social strife was being worked out as lots of jawing, squawking and head to head was occurring. At 1900 we set down anchor.

The next day, while working in a different waters, I had been investigating a path to cross through the rocky islands that extend off the South of Bimini. For two days I paid close attention to any boat traffic going Eastbound and noticed they all chose the same cut through. I conferred with the director about anchor depths, looked at the GPS and depth charts and concluded that route I'd seen all the other boats taking would be our way over to the Sapona. So, when we had a good mid-day period to break for lunch, we made the turn and ventured towards it.

The Sapona was a freighter built in Wilmington, North Carolina during the WWI era. It was made entirely of concrete due to shortages of steel during wartime. A developer in Miami bought it and moved it to Bimini in the late 20's using it for gambling. It was run aground during a hurricane and has not moved. During WWII, the US began using it for target practice, flying over it with airplanes and dropping bombs onto its robust, concrete and iron frame. According to wiki Flight 19, during a bombing run, had disappeared somewhere in the area over Hens and Chicks.

I love being on locations that are rich with history. You can feel it in its structures when around these special places. The Sapona was an waterman's dream adventure. It stuck high out of the water, but had been bombed just enough to blow out most everything short of its skeletal frame. The surging waters pumped through its open walls and while inside, had to be careful not to get tossed about.

(Southern stingray, facing bow, stern wall, beneath the surface )

(Over under digital composition by yours truly)

By Tuesday, it had been three days since we had a dolphin encounter and it was our last full working day. We had seen a singular dolphin out on its own. A speckled named Mola. We picked up her trail one late afternoon and followed her for half an hour. We were hoping she would reunite with other dolphins, but that moment never came. Seeing a solitary spotted dolphin, especially a young one, is not common.

We spotted her again the next day, about where she left off before and this time we put two researchers in to evaluate her state more closely. She was meandering along at a slower than usual pace, picking up sargassum from the surface and playing with it a bit by herself. In the water with the researchers she did take to sargassum play a couple times but resumed her slow, meandering travel towards who knows where. Guesses were made, but nothing revealed itself for why she was alone. She had a remora stuck to her belly, which can be quite a nuisance so she took a couple leaps into the air to come crashing back down onto it an attempt to shake it off. A couple of her leaps put her on plane with the upper bridge, about fifteen feet above the water.

After much wishful thinking over supper, we put it out to the Universe that we wanted to see seventeen dolphins the next day. Sure enough, by 10AM we came into a group of fifteen plus. Twenty in total that were grouped together in a tight travel formation. We attempted a couple jumps, but to no avail as their plans would not be halted. From the bridge I could see two older males simultaneously flip over so that their stomachs were up and tail slapped the water repeatedly, perhaps to signal to the others that they should keep moving. As I've described before, its hard for the juveniles not to become distracted.

The final night we surprised everyone with a special anchor hold. On this night, we would set down tackle at the Northwest corner of Great Isaacs Cay, just beneath its looming 151 foot tall lighthouse. Before dinner, five of us took off our researcher pins and swam to the island as explorers. It was an incredible experience. The rocky landscape on this island was hostile, rugged and decrepit. The lighthouse, which had a newly installed solar panel, does not seem to be working as it should. Only a faint glow could be seen once the sunlight was fully extinguished. There were small house like structures surrounding the base, all of which had crumbled with exception to the walls and portions of their rafters. It was fun to imagine living there, with only a small, dense section of Australian pines. As with much of the Bermuda Triangle, so too did this island lay claim to a mysterious disappearance of two lighthouse caretakers. There was barely any soil, but patches of grass grew from the razor sharp limestone with the surrounding water crashing onto the island from all sides.

The island rose up maybe fifty from sea level and I imagine a hurricane could have shot geysers of spray past the top of the tower. There were terns swooping and cackling all around us. It was so noisy, but sitting for a minute to imagine this scene like that of an asteroid hurtling through space was a fanciful moment. I took lots of photos of the group as we were drinking in the celebratory fun. For two of the girls, this would be their last night of the season. I think it was a great finish to their summer story. They went back to the boat while the co-captain and I slowly made our way back to the jagged shores where we had stashed our fins and masks. The sun was setting over top of the sailboat we anchored next to and I dove down into the near dark, fifty foot waters to look up at the last shimmers of light on the oceans' surface.

(there are no closed doors, there are no stones unturned, researcher by day, portrait of Isaacs)

All night you could hear the terns swooping and calling out to each other. We thought maybe they had lost their minds and desperation caused them to fly around in circles, but with nowhere to go except back down to the island. Being at sea can have that effect on you: the feeling of losing one's mind to the madness of isolation. Even with people aboard your ship, the grandness of the sea, with its horizons stretching out towards what feels like infinite, only to be perfectly segmented by the ever-changing, color scapes of the sky, captures you -- taking you into the hold of its fluid, blue form.

It took a lot of work, but I leave you fine folks with a video collection for WDP Trip #7.

Comments