EYE OF THE STORM - WDP TRIP 3

- mandog

- Jun 8, 2018

- 21 min read

Updated: Mar 7, 2019

June 08, 2018

Summarizing the third trip of the 2018 Wild Dolphin Project field season

An interesting thing happened on the third day of the third trip with the Wild Dolphin Project. On this particular voyage we were spending some time up in the Northern Bahamas, with our anchor point each night being along the shoals of a particular cay. In the morning, as we took off to motor around, I heard an old, croaky voice repeatedly calling for Old Bahama Bay over the radio. His voice, so soft and expired was barely audible, but kept repeating the call. The vessel never detailed any issue or concern, so I put it aside as we continued the thirty mile voyage past Memory rock, the last point of land.

The sand ridges along Little Bahama Bank are a feature of itself. The clouds reflect a green glow from the soft, white ripply bottom beneath the ocean's surface. Along the way, multitudes of patch reef appear and give way to the bright blue, seemingly dyed colors of water. We were out to retrieve the listening EARs we had placed a month prior. Knowing that a little bubble time was in the forecast for me, I was eager to get get there. As the color turns from a rich, royal blue to a slightly turquoise, but equally electric and vibrant shade, the destination is now within sights of the naked eye.

A few of us stood at the bow as we motored closer to the GPS marked location. Sure enough, I saw its profile there in the less than thirty feet of water. I indicated where to move the boat so we could safely drop the anchor. I geared up, while a few others played with their different equipment. It's nice to see everyone has a 'toy' to play with while out on these expeditions. Camera equipment is being tweaked, aerial drones are taking off and landing, underwater drones are circling and becoming lost underneath the boat, acoustic recorders are there to catalogue what each instrument adds to the frequencies to be sure not to disturb the primary focus, which is cetacean data and us there with our scuba kits ready to go retrieve the recorder and its data.

Finally, we were ready and I back rolled in, flipping my fins up and submerging straight down to float effortlessly above the soft, sandy bottom. Looking up from the stern, the clarity extended well past the bow to the anchor line. I lay on my back and practiced blowing bubble rings as I watched the next diver make his entrance. Going from a free fall to suddenly being submerged in a minimal gravity environment, the speed instantly switches to slow-motion. The water and negative buoyancy help guide my dive buddy down to the bottom next to me. He sees me enjoying myself and takes a minute of his own to take in the sensations. He is enjoying his time underwater as much as I am. He stops to check out the razor fish (jokingly referred to as dolphin potato chips as they are not a complete meal) that are all waiting anxiously above the sand, ready to disappear in the blink of an eye.

I blow a few more rings for him to enjoy and then check that he's okay before moving up the anchor line. The current was pumping pretty good. I glide over the top in a streamlined position while he uses his hands to inch his way along the bottom. I've worked years at perfecting my buoyancy and how to roll onto my back and not crash into the bottom, how to glide delicately close to sea fans without disrupting their waving cadence or twisting myself down into the cracks and crevices of ledges without touching any of the jagged, rocky surfaces. As I worked over the EAR, I too like to practice my buoyancy in a hover and keep myself up off the surface. It's a practice I truly admire when I see it in others, photographers or lobster catchers as examples. I enjoy the moments where I too can demonstrate the care and consideration of the fragile and sensitive ocean topography.

The block to which we had mounted it to was mostly covered by sand and only the EAR was exposed. We talked about attaching a short float line to the block, but if it were to sway or rub it could possibly emit a sound that the recorder would then pick up and add to the data pile of recordings. In one month it had made over eight thousand, thirty second recordings. There will be software used to filter through the data and detect the ones containing dolphin frequencies. As a joke, my dive buddy and I always cup our hands around our ear and point our heads to the EAR device.

We removed the device and returned it to the boat for disassembly, extraction and downloading of the hard drive and reinstall everything to be put back in place for another month's time. As they worked on that, I took off my scuba equipment and continued to freedive with another boat mate. The waters here are one of a kind, and the only thing worth getting out for was a blown toilet valve. So, I conveniently decided to stay in until the EAR was ready for re-deployment.

At twenty five feet I could easily get myself onto a flat back position on the bottom and practice blowing bubble rings on a single breath. It's much harder obviously as the lung capacity is not the same as on a scuba cylinder. As frustration surmounted I continued to stay down attempting to get three or four more out before going back up.

The boat pal had pulled in a trash bag we'd seen floating by, which happened to be a fish hotel and carried with it two juvenile bar jacks. She extracted the trash from the ocean, but it's an odd situation with things like that. Now the runners had no cover and fearing for their protection, swam around us refusing to leave our side. They moved from in front of my mask to behind my back and as we passed them off from one to the other. Neither one of us could ever manage to lose the tail. Even as we freedove down to the bottom they would follow us there and back. They were too close to my camera to really even get a proper focus on their teeny, little fish bodies.

After awhile the EAR was ready to go back in and I geared up to, well, return to the water I had never left. We manually heaved the block up out of the sand, moved it from the depression it had created, tucked the EAR back into the hose clamps and then posed with our usual series of joking gestures. Fist bumps, mimicked ear moves and lounging with our hands behind our heads; all signals that we were enjoying the laborious tasks we had to do in the luscious, eighty degree Bahamian waters.

I must've laid there for about fifteen minutes blowing rings at the surface. It's a newfound addiction, but at the same time a chance to practice and I simply did not want to get out. I've said before that I could die down on the bottom, but people always perceive it in the obvious, off-putting way. I just mean, I am so at peace, so in love with the moment, so completely comfortable, relaxed, fulfilled and content with life that I could transcend this body and release energetically back into the cosmos.

At that very moment there would not ever be a more serene and more fitting opportunity for that transition to happen. And so, as the nagging feeling of people are probably expecting my return kicks back into my delighted and distracted mind that is laying there looking up at the sun beams radiating through the beautiful waters, I reluctantly leave my chosen watery spot to fin back to the boat. I watch the motions happen in reverse as my dive buddy rises to the surface and ascends the platform.

Two swimmers are over head and I send up a couple bubble rings to greet them. I am really obsessed with these! Mainly, because I realized how terrible I was until the field assistant showed me hers and I was astounded at her ability to connect multiple rings or get back up to the surface and swim down through her perfectly sculpted creations. Another researcher is there swimming on the surface and I capture her duck diving through a ring while another person films.

We were letting everyone get their fill of this one of a kind swim spot. While giving the last few pulls to the anchor line the spotter and I commented on the niceness of the pool-like water conditions. Not any sooner than we had finished agreeing to this, I looked up towards yet another hazy, storm-filled horizon.

Leaving this remote territory is always a mixture of emotions. For one, it is so pristine and beautiful and while being isolated in the Caribbean, feeling like you have it all to yourself, it also occurs that two, you are miles from any resource and being there is an obvious cause for concern. So, commencing the voyage back to our nightly anchor hold lessens the worry and provides a much needed sense of relief when land is again visible on the horizon.

The presence of an intense voyage was now making itself known. It has become a recurring theme being stuck in storms. We watched as the walls of rainstorms went from being on our Western flank, to up ahead on our Southern heading, to then partially encircling us to our East and then finally, as the Northern direction we were traveling from, was now unified with a blanketing gray wall. It was time to batten down the hatches and send everyone inside, less the captain and I.

We slipped into our rubber, save-our-ass-from-lighting boots and hammered into the direction of the ensuing storms. "Here we go," we said, as we go from placid and gentle to white knuckle adrenaline-filled boating. The wind starts to shear and except for the whites of the now cresting waves, the ocean has turned towards a violent shade of purple. We are eating the waves at a head-on direction and the boat starts to rattle and roll. We've got maybe about fifty feet of visibility in any direction and are charting using the GPS to avoid hitting a shallow sandbank known as the dry bar.

Lightning is spider-webbing across the sky, striking in all directions. Bolts were so bright that it's electric purple hue was illuminating our skin tones as we exchanged oh shit faces. We tell stories to pass the time, but mostly its done just to keep our minds off the pressing fact that the passengers are some kind of lucky that they don't open up the hatch to see us fried like chicken tenders with the auto-pilot still keeping us underway. We wouldn't give up that easy, though, and maintain our composure to motor safely all the way through the storms. After about four hours of blasting through it, we finally make it back down to Sandy Cay.

On our way out that morning, we had heard a distress call go out over channel 16. The call detailed an elderly couple that had broken their bow sprit in the night and were unable to retrieve the anchor, causing them to be fixed near a particular landmark. They were somewhere in our vicinity, but a US Navy aircraft had been relaying their messages to the coast guard. We recorded their information and saw no reason to intervene. Now, a half-day later, as we were approaching Sandy, another distress call was coming over the radio. This time a vessel closer to the main island was hailing. The operator, named Bob, was unable to get the anchor to set and in the pressing waves from the squall, was drug back towards the rocky shore. With each passing swell, their hull was banging on the bottom. While his situation was probably very unnerving, his conversation over the radio was comedic gold.

He was communicating with the coast guard about gaining assistance. Running through their protocols, they had him confirm if he was in fact making a mayday call or not. To which, he confirmed he was as he described his boat thumping and thought he would possibly have to leave his vessel and enter the water. His repertoire over the radio was giving us more of that belly-aching laughter. Maybe it was that, we too, had already been unnerved and needed some form of selfish comedic relief for ourselves. This seemed like the next best thing, but I have spent a lot of time on the water and around VHF radios and never have I ever heard a discussion quite like this.

Bob was in one moment feeling like he was being jerked around by the coast guard for requesting registration paperwork over the radio, calling a Bahamian number and following its prompts only to continually get an answering machine or a number to text, being frustrated by a vehicle parked on the beach and not offering help, to then calmly stating he has great wisdom of the coast guard as he had a cousin that worked there, back agitated and perplexed by the notion of a plane offering assistance and finally commenting that he had taken a tour of that particular plane as it flew over.

The wife had come on the radio a few times and actually provided tactile, detailed information such as their degree of listing and a situation that was more clearly explained to the channel operators than using 'Bob' language like violent thumps and mechanical spaces. The coast guard did send out a plane to do a flyover inspection of their situation, stating that they had rapid bail out pumps and a small raft that could be delivered, but none of which seemed it would help Bob's situation because, I quote, it was a "fairly easy swim to shore." I listened as Bob refused to leave his vessel and kept insisting he would to stay until he was ultimately forced to leave it. I was unaware, however, of the ramifications of such an act. Stranded vessels are opened up to a number of salvage claims, but it takes time for those to take place. Regardless, the wife, Linda, was at one point asked how the weather was down there, and she replied, "It's raining" in a satirical and unamused manner.

This 'conversation', and I use the word conversation to describe what was illicitly occurring on a hailing and distress channel, was the unfolding saga of Bob and we were the audience. I would run down the stairs and into the salon to update people as to what was happening. As dinner items continued to get prepared, I would bring down each development as they were more unbelievable and comical than the last.

After hours of these exchanges, the sailing vessel from earlier comes back asking if the coast guard was ever able to reach Towboat and if they had an update as to their response. The coast guard pilot says he was unaware of their situation, but later after talking with his command post was updated as to their story. He comes back with, "We were under the impression the coast guard had passed the call onto the royal Bahamian defense force and they had deemed it resolved." The sailing vessel informs that no help had been received and their location remained the same. The old, croaky voiced man said he had spent all day attempting to hoist the anchor manually, but was unable to do so. Their son was expecting them mid-day back in Fort Pierce and they requested a call be made to him to notify of their situation. It was such a sad contrast, as a stranded, elderly couple were hours away from any land, had broke their sprit the night before in violent storms, spent the entire day trying to raise the ground tackle and remained unrelieved from any support while Bob is refusing to swim 15 minutes to shore and having a two hour conversation with multiple agencies.

After putting Bob in touch with a commercial salvage vessel en route to his location, I watched as the coast guard plane I had heard communicating ping-ponged across our bow going from Bob's location up towards the location where the sailing vessel was located. It was a very surreal and humbling experience to be between a pair of maydays being called forth, while having weathered the exact same systems.

Thankfully, us savvy salts were skilled enough and certainly way more lucky on this day than those persons and set down anchor safely. As the sun began to fall between the stretched out storm clouds, I watched as the coast guard plane made one final pass before turning West and disappearing into the waning, multi-colored sunset.

The next day we made the crossing to Bimini where we would spend the remainder of the trip. The weather was much calmer. Along the way we found a large, floating tree trunk to which the captain snapped quickly into fish mode and threw out the trolling lines as I slowed the RPMs and steered us near it. On the first pass a rainbow runner took hold of the tackle and was quickly reeled in. I had seen flashes of green beneath the surface, indicating there were mahi's there. So, we circled back around and put out a big game lure for any possible wahoos lurking below. The second pass revealed some triple tails also being there, but nothing took hold. The tree trunk continued on its course as did the Stenella.

We were now set up in Bimini and ready to work with the dolphins. We had a good day of encounters, with operational weather. Storms were always on the horizon, but we took full advantage of the operational hours, landing encounters in the periods following breakfast and after our lunch-time swims.

The next morning, while on the bridge for her six am watch, Dr. Herzing and I had a very good and thorough conversation regarding the study of the species. She explained to me her thoughts on how anthropomorphism can actually be used as a tool to understand things and not so much of a hinderance. It's our way into being able to interpret life as another species, and sometimes it can provide insight if we don't take it too far. We talked a lot about how to be inclusive with wild species without being invasive, but at the same time perhaps it's a path towards reconnecting with nature. I commended her on the approach she takes of going for long-term data and always reminding people its not about us, it's about the dolphins. She made me laugh as I mentioned some of the film crew with us were interested in interviews and face time of her and she gave a comical snarl saying for them to "pick another face." It just goes to show her interests are not self-fulfilling. She has an objective and it is to provide the clearest and most in-depth understanding of this species with the least amount of impact possible. She is determined to not let herself get in the way of that.

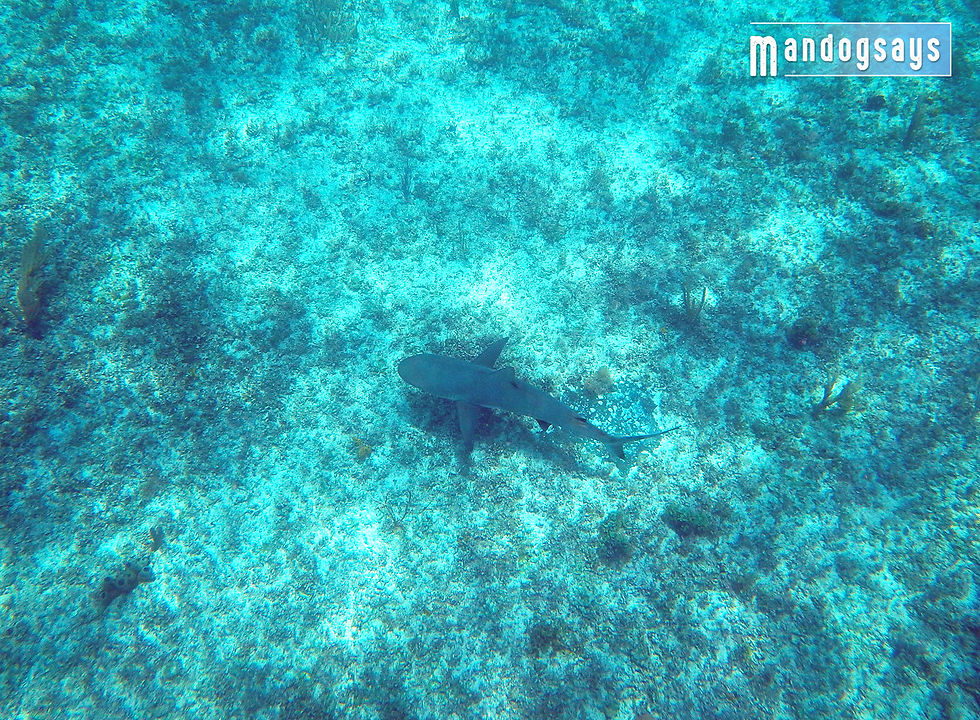

We continue to have good encounters, capturing amazing behavior on film and the guests are thoroughly enjoying their time in the water. We had clear enough weather this time to work out of the cover of the island more. We decided to venture up past Hen and Chicks towards Isaacs to go snorkeling for lunch. It was an incredibly cool spot, with long, low-relief ledges and tons of marine life. As soon as we hit the ledge, a small, juvenile reef shark was hot on our trail. I went down to evaluate its comfortability with divers and it showed malevolence, refusing to leave our side.

Tracking along the edge, I see the captain dive down and a few juvenile hogfish are pecking at the sand. Then, I see a stud come ripping past. In the flash of an eye, he has let loose a shot, the fish has shaken the slip-tip and dove beneath the ledge. We watched the area to see if it would reveal itself again, but before we could even try an inspection dive, the men in gray suits were already on scene. First, the squirrely, side-ways looking reef shark I expected to be there, and then two, three, finally a fourth, very large reef shark had arrived. They were circling the area intently, not giving us much leeway to do an inspection of our own. I scared off a few just to look beneath the ledge and had seen no such fish, realizing the ledge was a very shallow relief and it must've swam carefully along it to be undetected from above.

I spot the sharks circling a corner behind us at the start of the ledge. Maybe the hogfish had made a darting move there? We swim over to it, but still no fish. Then, I see a rock out in the open with a six foot nurse shark circling and scuffing up the sand, sniffing with intention. I point to it, saying it has to be there.

The reefies were circling above the rock and I free dive down amongst the army of sharks. I look underneath the edge and see a mammoth snout. It was sitting sideways trying the fabled hog tactic of sucking itself to the top of the rocks to trick predators into thinking no one was home, but the rock was simply too small. He had enough room on all sides where no shark could get to his flesh, but there were multiple access points. The nurse shark went from every angle attempting to wriggle its head in and even a few reef sharks tried getting their noses in.

We float above contemplating the options here. I said I could maybe spook enough of the sharks off for long enough to give the captain a chance to dive, get a shot in, pull it straight up to the surface and we boogie back to the boat, but it looked very risky and not a single shark had bought any of the bluff tactics yet. As we are discussing this, I see a a new character emerging. A long, wide-girthed female nurse shark swim in with a bonafide objective. I dive down to get a better look. She breaks from her course towards the rock and comes right up the water column towards me. I kick backwards attempting to use my fins to alter its course. Without pause it descends back down goes directly for the rock. I pop my head up laughingly and remark, "Look at this meat-head, no way she will be able to squeeze herself in and get it!" She ravenously circles the rock, billowing out clouds of sand as she puffs aggressively, twisting herself at each angle trying to find the one that lets her suck out the fish.

We watch in wonder as this huge beast hijacked the scene. She approaches the angle I surmised had the most access and then, right before my eyes, I see the three hundred pound rock lift up and crash back down loudly. My eyes go wide, jaw hanging gaped in the ocean water. This creature, whom I just doubted, dead lifted a piece of the ocean floor with its own head, tried to take the fish and nearly crushed itself in the process. I see it swim away with all the sharks following suit. I say, "This is your chance, all the sharks are gone! I will go down to see if its still in there, then you follow after." After I go to look, I am surprised to find nothing but an urchin where previously a hogfish had been hiding. The captain dives down and confirms that where there once was a fish, now there is not. We look at each other bewildered.

Stumped again at where this fish has gone. I dive down to inspect once more and again the girthy nurse shark has returned. She repeats her charge at me in the water column and I deliver more backward fin kicks in its path. It turns to swims towards the captain's scented pole spear as if it desires more. It comes right up nose to nose with the spear before quickly turning away to flee the scene, this time for good.

It must've gotten the fish out when it picked up the rock, but for it to swim back around after it had eaten it was completely baffling. It was a real head scratcher, and certainly a reminder that sometimes we are not on top of the food chain. On the way back to the boat we met up with a few other snorkelers and checked out an active little pass-through on the reef. The "school house" of schoolmasters made their patterned, routine loops. It was a vibrant and happening place, but I was still reeling from the sharky behavior. Clearly I had a lapse in awareness. No longer in diver habituated Florida, but instead I was swimming in the wild waters of the Bahamas.

We had a few good days of encounters with a lot of storm dodging for the remainder of the trip. This time of year is apparently the dolphin's mating season and most the active males were in rut. Nearly every encounter contained courtship between the dolphins. The fused males (+15 years) are the only ones capable of siring a calf, but we see plenty of juveniles attempting to practice what is taught to them by their elders.

On one encounter, the young males, in attempt to be noticed, were repeatedly launching themselves into the air and crashing down onto their competition. From the boat, it was quite a spectacle as we can see much more happenings in the distance than the limited view the swimmers get.

The last day, we actually had a chance to get in with the bottlenose as they were crater feeding. Sensing no objection to our viewing, we notified another operation that was attempting to film on the subject matter and left the area. We later got the karma sauce passed back to us as the same operation pointed us in the direction of a dozen Atlantic spotted dolphins. We were mid-way to our anchor spot when the skies magically cleared up and we found the group we were directed towards just between two other dolphin expeditions that were also seeking out their days' last encounters.

Earlier, we had given a very energized and enthusiastic trio of spotteds (Polaris, Arugula, Rue) a bow ride and they had now returned to the group of twenty five for our last encounter of the trip. It was a really great finish.

On the forty mile voyage back from Bimini, I, lone on the wheel, had full disclosure from the captain to slow it down should I see any good fish indicators. He went to rest and work on the customs paperwork. I put on some tunes and kicked it back as I edited my stories, glancing around every second as the autopilot kept us in a Westerly direction. Passengers would come and go, but only stay for twenty minutes at a time. Much can't hang like I can for the entirety. It's exhausting, but I spend all day on the bridge. Would I rather be snoozing in a bunk, have my nose in a book or looking out across the open ocean, full of surprises? The choice is always clear, I choose ocean!

I pass through a wind slick and see it is loaded with grass. As good a sign as any. I slacken the throttle as one of the research assistants was about to go back down. I yell, "GO GET THE CAPTAIN! Tell him it's grass and birds!"

Up ahead, I see a frigate chasing a small gull. It was definitely the spot. The weed line was running parallel to the shore and the gentle winds were keeping it all together. I start my arc back to put us adjacent to the slick as the cap pops his head up. I say, "Birds. Weeds. Get it ready. I'm putting us alongside it."

He gets one line out and starts on a second. We're running medium and heavy tackle. As soon as he tightens the drag on the heavy, 50 wide reel, the water pressure causes the lure to rise up catching the attention of what we believe to have been a wahoo. It smashes the tackle, taking out line at a ferocious rate. The captain tightens up the drag more once he sees the back line starting to appear on the reel. The tension causes the hook to rip out and the fish was off. I also mistakenly slackened the speed, thinking it was a smaller fish, and this too perhaps allowed the fish to slip the hook.

The whole series took maybe five minutes to go from finding the slick to getting a wahoo to smash the line. Our adrenaline was surging! The cap slaps his head and grimaces at the thought of losing such a fish. I tell him it's okay, let's circle back and I start scanning with the binoculars for where the frigate was. Finding a break in the line, I cross through so not to snag any sargassum. Up ahead I can see fish hammering a bigger patch of grass and set the auto pilot to sweep alongside it. I run down the ladder and say, "Get ready! We're about to get a hit."

As one of the passengers was standing nearby, curious to the activity, BAM! The line begins to buzz with another fish on. The captain starts to crank the reel, but sees the passenger and passes the rod to her. She stands with one hand holding at the base of the grips and the other further up on the mid-section of the rod. He looks sideways at this awkward assembly of hands and says, "No no, you gotta reel it!" She fumbles with the mechanics for a few turns and then starts to get the hang of it.

The shimmering, electric green flesh of a mahi is seen on the surface as she pulls it in. When it was pulled up to the stern, the captain takes the rod and lays it down, holding onto the line pulling it up and over the transom. He holds the fish close to his body, sure not to let if flip over the side. He works the hook loose and holds it sideways as depicted by every angler. She poses in a few photos holding the tail as he still firmly grips it by the gills. The fish is killed and put into a bucket with ice. I cross back through another break in the weed line and start to retrace my path hoping to reconnect with the monster that slipped the hook the first time.

We manage to get another mahi on and after getting this one to the boat, determined it was too small to keep and tossed it back to the sea within a matter of seconds of having it on the boat. The fish event was over, so it was back to our Westerly course.

Eight miles from shore, I slow down again and tell someone to go and get the cap. We've got another frigate up ahead and its flying low. It was following a freighter going up the coast. We dont run with the lines out as we can't hear it from up on the bridge if a fish does take line, but when we see signals like this, if acted with enough efficiency, we can take advantage of the situation. We're also not a fish charter, so fishing isn't overdone. Enough to catch fresh fish for a dinner and allow passengers the chance to be a part of the catch.

The captain joins me on the bridge and he waits to see what the frigate does before he acts. The frigate starts working its way towards the boat, circles low, nearly swoops beneath the bow and then takes back off as we seemed to have intersected its path. He'd seen enough. He goes back and puts out a line. BAM! Instant hit and another schooling mahi was reeled onto the boat. There were weed lines all the way to the inlet, but we had enough excitement for the day.

On the back deck I could see the impressive green colors being cut lengthwise from the long, angled body. Its stomach contents inspected as curiosities amount. Small trigger fish the size of nickels and quarters inside. I looked at the fish, noting which one was which and the first one we caught I felt connected to and decided it would be appropriate for me to consume a portion of it. I ask cap to save me a few pieces of it.

That night, I blackened the filets, heated some butter in a pan until it smoked and enjoyed the best fresh fish I can ever remember catching, cooking and eating.

Lastly, a parting gift! I leave you with a video of our sharky adventures at Isaacs!

What a shark tale! Fabulous photos. Bubble obsession justified ;)